The shadow economy is part of the business model of labour exploitation and human trafficking

Source: HEUNI, Anniina Jokinen, 16 March 2020

A growing number of labour exploitation and human trafficking cases have been uncovered in Finland in the cleaning, restaurant, construction, agriculture and production sectors. The European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control (HEUNI) has studied this issue for over 10 years.

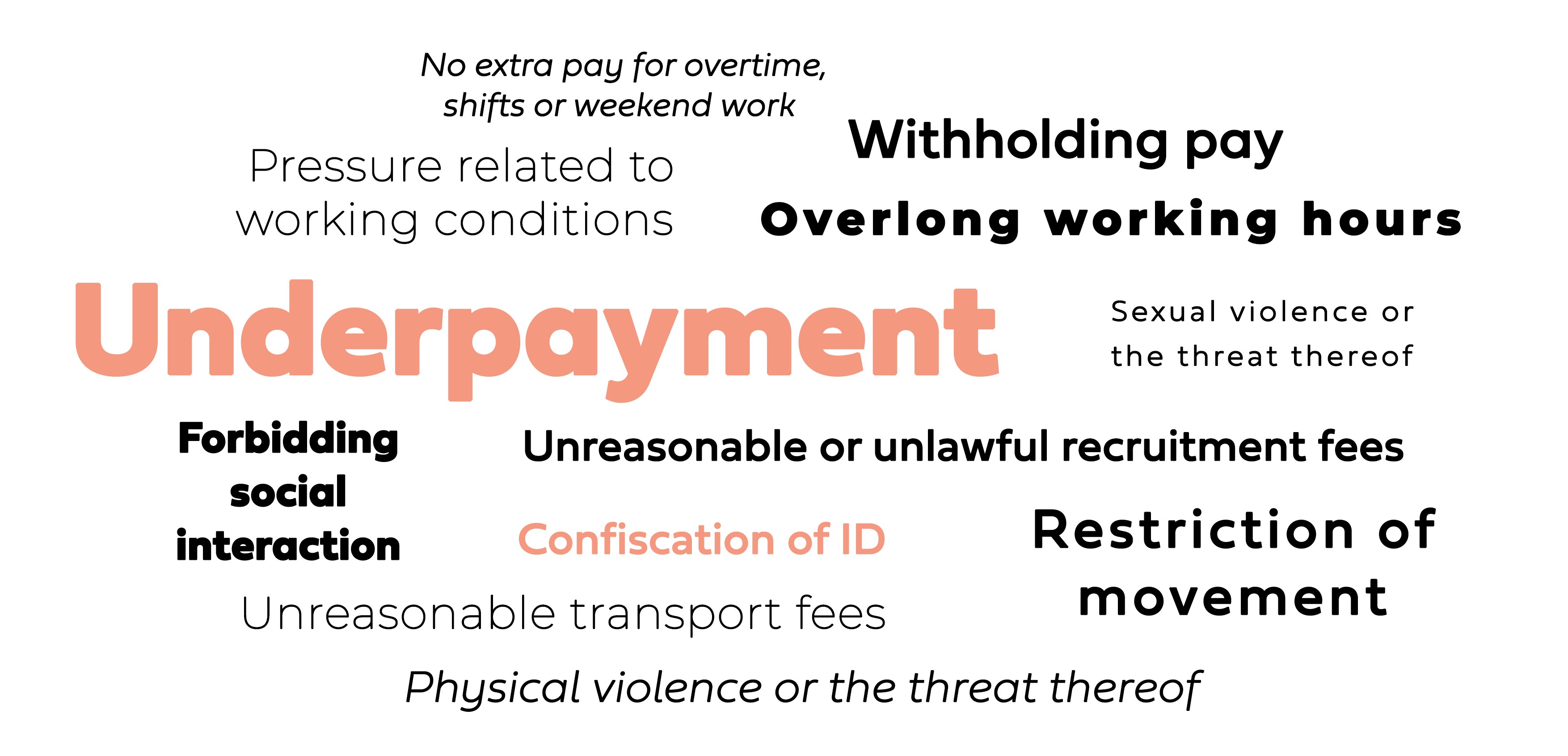

According to HEUNI’s studies, labour exploitation is financially profitable, and the risk of being caught and punished is usually low. Unscrupulous companies and dishonest entrepreneurs take advantage of legal structures and means to maximise their profit and hide their exploitative activities from the authorities. On paper, everything looks to be in order – but in actuality, migrant workers in labour-intensive high-risk sectors are often not only underpaid, but also subject to other forms of exploitation (Figure 1). The shadow economy is also strongly linked to this phenomenon.

Figure 1. Forms of labour exploitation

Labour exploitation and human trafficking

Not all labour exploitation is human trafficking, although as a phenomenon it often amounts to the same thing, the exploitation of the migrant worker’s vulnerable position and lack of awareness in various ways. Human trafficking is a crime with diverse facets. It comprises three elements: the act,, the means and the purpose. In human trafficking, the criminal abuses the victim’s vulnerability, trust or dependence and subjects him/her to exploitation – in this case, forced labour. Forced labour does not necessarily entail extreme coercion, violence and control of the worker; it is also vital to consider subtle means of control, such as the factors that make it impossible for the worker to leave the work. These could be dependence on the employer due to debt and vulnerability due to a lack of awareness and options.

It is not often easy to draw a line between labour trafficking and ‘mere’ labour exploitation. Another relevant key type of crime in Finland is extortionate work discrimination, which is defined as a crime related to human trafficking. In extortionate work discrimination, the worker is placed into a considerably inferior position through the use of the job applicant’s or the employee’s economic or other distress, dependent position, or lack of understanding.. Generally it involves underpayment and poor working conditions. Extortionate work discrimination applies to situations involving discrimination, while human trafficking is a crime against personal liberty. Human trafficking is involved if the person does not have actual means to leave the employment relationship because s/he is under the comprehensive control of the employer.

In many cases, the authorities only uncover some of the crimes involving exploitation. Human trafficking is a hidden form of crime and its victims are often afraid of the authorities. For this reason, potential cases are not necessarily investigated or defined as human trafficking – or even as labour crimes – and are instead treated as financial crimes, such as tax fraud.

Business model of labour exploitation

The EU-funded FLOW project coordinated by HEUNI examines the links between labour trafficking and financial crime in Finland, Estonia, Latvia and Bulgaria. At the end of 2019, a report that sheds light Shady Business (PDF 15 MB) on the business model of labour exploitation based on case analysis was published.

Unscruplous entrepreneurs generally focus on two primary means of making a profit: reducing costs and generating revenue by charging workers for a variety of extra costs (Figure 2). The cost reduction strategy involves cutting labour costs by means such as underpayment, making workers work longer hours without paying statutory overtime, and evasion of employers’ contributions and taxes. The revenue generating strategy in turn is based on collecting upfront fees from workers in connection with their pay or training, for instance, and overpricing a variety of costs (incl. commissions, transportation, accommodation, food, clothing, work equipment and tools). Most commonly, labour exploitation involves substantial underpayment, with the employer deducting a variety of charges from the wages, such as for commissions or accommodation, food and tool costs. This in turn can lead to indebtedness and greater dependency on the employer.

Figure 2. Business model of labour exploitation

A structural problem

Labour exploitation and human trafficking are fundamentally structural problems. The risks of labour exploitation are increased by a great need for labour, which fluctuates strongly, as well as the need for flexible and temporary workers. The risks increase in low-paid fields and seasonal work and in the context of outsourced services and long subcontracting chains. These methods – which in themselves are fully legal and commonly used – enable employers to exploit migrant workers in particular. Criminals take advantage of legal business structures. For instance, they make use of cascade subcontracting, fronts and shell companies to post workers from one EU country to another. This enables the criminal to avoid the statutory liabilities as a contractor and other obligations, keeping the company’s records clean and hiding the operations from the authorities. Companies that operate legally may also become party to human trafficking through subcontracting, for instance. For this reason, HEUNI has recently engaged in and developed in cooperation with companies Guidelines for businesses and employers for risk management in subcontracting chains (PDF 3,4 MB). The FLOW project is also creating a practical toolkit for companies to prevent labour exploitation, with a particular focus on developing its own inspections and monitoring mechanisms.

Tackling human trafficking requires co-operation

Human trafficking and equivalent phenomena can come to light in sectors monitored by many different authorities – for this reason, cooperation between the authorities and stakeholders is important. In addition to the police, the occupational health and safety authorities, tax and other law enforcement authorities as well as organisations and trade unions can identify cases that include indications of labour exploitation and human trafficking. The FLOW project develops guidelines targeted particularly at the law enforcement and occupational heath and safety authorities.

To prevent human trafficking, it is also important to intervene at the right time into less severe forms of labour exploitation and financial crime. However, from the perspective of the victims, it is important that cases with indications of trafficking are identified and investigated as human trafficking. Victims of trafficking have the right to support from the Assistance System for Victims of Human Trafficking [.fi]›. Victims are provided with accommodation, healthcare and social services, legal counselling, support for the criminal process and assistance with applying for a residence permit. However, victims of extortionate work discrimination and other labour crimes do not have access to these services. For this reason, it is very important to raise awareness of human trafficking among the authorities and other stakeholders.

More information on human trafficking is available from the ihmiskauppa.fi [.fi]› and Victim Support [.fi]› sites.

More information on the FLOW project is available from HEUNI’s English-language site [.fi]›.

HEUNI reports on labour trafficking:

Trafficking for Forced Labour and Labour Exploitation in Finland, Poland and Estoni a (PDF 1,6 MB)